2K7 in Review: My Favorite Albums, #2

The vacation has sadly come to an end. Sassy Frass and I recently returned from a whirlwhind tour of the northwestern U.S., a trip thankfully financed by my loving parents, as I certainly couldn't have afforded it right now. Highlights included my second-youngest cousin's memorable rural Washington wedding, paddle boating, the Experience Music Project/Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame, orca spotting, Seattle's oldest surviving punk rock club and the consumption of much seafood. For the forseeable future, I will be busy with preparations for the big move and the Pitchfork Music Festival. While you await the end of this damn list, read these chats I recently conducted with two radically different psychedelic music makers: Nachtmystium and Mickey Hart. And then there's this...

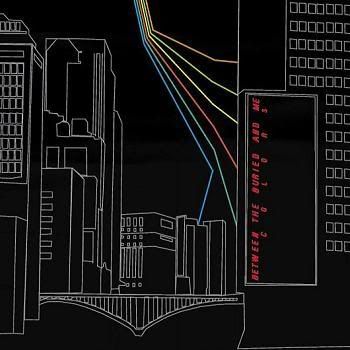

2. Between the Buried and Me, Colors (Victory)

2. Between the Buried and Me, Colors (Victory)

We return to the eternal push-pull of the bombastic and the soft, the euphonous and the dissonant, the traditional and the experimental. Variety is crucial to any fresh metal band hoping to sustain interest in an era when the genre has been commodified, chronicled, recycled, ridiculed and written off for nearly 40 years. And, my, how the technical sector of metal has flourished in recent times, illuminating a number of proficient young players who typically either put on dazzling clinics of which an audience can remember absolutely nothing, or squeeze their abilities into a low-achieving radio fodder format like so much ground pig snout into a sausage casing. That's why Colors is the most impressive metal album of 2007. Even though it comes from a bunch of short-haired dudes with a strange band name and plenty of trend-friendly deathcore and emo elements, it overflows with a singular identity that makes a rote catalog description like "Dream Theater meets Beneath the Massacre meets Pink Floyd" (or their own "adult contemporary progressive death metal") truly useless. With increasingly impeccable genre mash-ups and mind-numbing twists of speed and texture, North Carolina's Between the Buried and Me has operated far above every sing/scream metalcore act with which they've been indiscriminately associated since their crackling self-titled debut in 2002. Most technically oriented extreme metal bands refuse to allow any sense of fun to seep into such densely intense music, but these dudes dare to peek from behind stern expressions while remaining deadly serious musicians - endearingly earnest ones at that. The sudden fragments of fragility and frivolity that flavored 2003's The Silent Circus and the savage cornucopias of 2005's Alaska showcased a very good outfit getting better and better, while 2006's pleasingly eclectic all-covers The Anatomy Of served as a guide to divergent sounds that coverge in the quintet's style. Wrapped in indie-style, geekily simplistic line-drawn cover art that capably heralds the mathy rainbows in the dark found within, the ingenious and addictive marathon that is Colors both encompasses and surpasses their past greatness.

All the band's trademarks (pummeling stompcore, mathy prog wizardry, triumphant harmonies, dreamy shoegazer pop and copious curveballs) are here, yet the fluid flow of ideas exceeds expectations. The tracks are appropriately sequenced without breaks, and although moments like the Arabian intro of "Informal Gluttony" or the creepy accordion waltz that intrudes upon "Prequel to the Sequel" immediately stand out, as opener "Foam Born (a): The Backtrack" regally portends with its gradual Queen-to-Emperor build, Colors is best experienced as if it were one long song. Tommy Giles Rogers Jr. is a rare modern metal vocalist who delivers harsh roars as convincingly as he does blissful Beatlesque harmonies, and his versatile performance here stands shoulder-to-shoulder with Scandinavian giants Mikael Åkerfeldt and Simen Hestnæs. Guitarists Dustie Waring (also of Glass Casket) and Paul Waggoner (Rogers' former bandmate in Prayer for Cleansing) put on a alternately fierce, jazzy, jubilant and playful clinic, spilling grindcore squeals and ginormous arpeggios that should send all those petulant little MySpace teengrind acts back to huffing paint thinner in their parents' basements. For your listening pleasure, I'm streaming the album's centerpiece, a pair of tracks both topping ten minutes. After a formidable off-kilter death/grind beginning showing off the chops of both bassist Dan Briggs and drummer Blake Richardson (another Glass Casket guy), "Sun of Nothing" goes all sludgy before relaxing with a segment of Floydian psychedelia, making a seamless transition to the delirious sprawl of "Ants of the Sky." Perhaps the best track here, the latter tosses in Pantera-ish lunkhead thrash, starry-eyed ambience and even a brief hoedown complete with hollers and clinking glasses before a finale that stacks riff upon riff as a monument to towering melody. With so many shades and textures to explore, Colors is never a chore despite demanding continuous attention for its 64 minutes, exhibiting the operatic range of your favorite "classic rock" magnum opus with a thoroughly modern approach. Between the Buried and Me's channel-surfing churn finally ranks alongside the finest cage-rattling caprices of Sigh, Mr. Bungle and Solefald - an imaginative, sumptuous, free-spirited feast that will remain one of this decade's defining touchstones for open-minded metalheads.

No official videos were made for Between the Buried and Me's Colors, but video "interpretations" of every song utilizing stock film clips are available here in the form of an album trailer. Also, here's a nifty live multicamera bootleg filmed in Texas last October.

"Informal Gluttony"

2. Between the Buried and Me, Colors (Victory)

2. Between the Buried and Me, Colors (Victory)We return to the eternal push-pull of the bombastic and the soft, the euphonous and the dissonant, the traditional and the experimental. Variety is crucial to any fresh metal band hoping to sustain interest in an era when the genre has been commodified, chronicled, recycled, ridiculed and written off for nearly 40 years. And, my, how the technical sector of metal has flourished in recent times, illuminating a number of proficient young players who typically either put on dazzling clinics of which an audience can remember absolutely nothing, or squeeze their abilities into a low-achieving radio fodder format like so much ground pig snout into a sausage casing. That's why Colors is the most impressive metal album of 2007. Even though it comes from a bunch of short-haired dudes with a strange band name and plenty of trend-friendly deathcore and emo elements, it overflows with a singular identity that makes a rote catalog description like "Dream Theater meets Beneath the Massacre meets Pink Floyd" (or their own "adult contemporary progressive death metal") truly useless. With increasingly impeccable genre mash-ups and mind-numbing twists of speed and texture, North Carolina's Between the Buried and Me has operated far above every sing/scream metalcore act with which they've been indiscriminately associated since their crackling self-titled debut in 2002. Most technically oriented extreme metal bands refuse to allow any sense of fun to seep into such densely intense music, but these dudes dare to peek from behind stern expressions while remaining deadly serious musicians - endearingly earnest ones at that. The sudden fragments of fragility and frivolity that flavored 2003's The Silent Circus and the savage cornucopias of 2005's Alaska showcased a very good outfit getting better and better, while 2006's pleasingly eclectic all-covers The Anatomy Of served as a guide to divergent sounds that coverge in the quintet's style. Wrapped in indie-style, geekily simplistic line-drawn cover art that capably heralds the mathy rainbows in the dark found within, the ingenious and addictive marathon that is Colors both encompasses and surpasses their past greatness.

All the band's trademarks (pummeling stompcore, mathy prog wizardry, triumphant harmonies, dreamy shoegazer pop and copious curveballs) are here, yet the fluid flow of ideas exceeds expectations. The tracks are appropriately sequenced without breaks, and although moments like the Arabian intro of "Informal Gluttony" or the creepy accordion waltz that intrudes upon "Prequel to the Sequel" immediately stand out, as opener "Foam Born (a): The Backtrack" regally portends with its gradual Queen-to-Emperor build, Colors is best experienced as if it were one long song. Tommy Giles Rogers Jr. is a rare modern metal vocalist who delivers harsh roars as convincingly as he does blissful Beatlesque harmonies, and his versatile performance here stands shoulder-to-shoulder with Scandinavian giants Mikael Åkerfeldt and Simen Hestnæs. Guitarists Dustie Waring (also of Glass Casket) and Paul Waggoner (Rogers' former bandmate in Prayer for Cleansing) put on a alternately fierce, jazzy, jubilant and playful clinic, spilling grindcore squeals and ginormous arpeggios that should send all those petulant little MySpace teengrind acts back to huffing paint thinner in their parents' basements. For your listening pleasure, I'm streaming the album's centerpiece, a pair of tracks both topping ten minutes. After a formidable off-kilter death/grind beginning showing off the chops of both bassist Dan Briggs and drummer Blake Richardson (another Glass Casket guy), "Sun of Nothing" goes all sludgy before relaxing with a segment of Floydian psychedelia, making a seamless transition to the delirious sprawl of "Ants of the Sky." Perhaps the best track here, the latter tosses in Pantera-ish lunkhead thrash, starry-eyed ambience and even a brief hoedown complete with hollers and clinking glasses before a finale that stacks riff upon riff as a monument to towering melody. With so many shades and textures to explore, Colors is never a chore despite demanding continuous attention for its 64 minutes, exhibiting the operatic range of your favorite "classic rock" magnum opus with a thoroughly modern approach. Between the Buried and Me's channel-surfing churn finally ranks alongside the finest cage-rattling caprices of Sigh, Mr. Bungle and Solefald - an imaginative, sumptuous, free-spirited feast that will remain one of this decade's defining touchstones for open-minded metalheads.

No official videos were made for Between the Buried and Me's Colors, but video "interpretations" of every song utilizing stock film clips are available here in the form of an album trailer. Also, here's a nifty live multicamera bootleg filmed in Texas last October.

"Informal Gluttony"

1 Comments:

Darker side of the moon: Nachtmystium shines black light on black metal

Black metal can take inspiration from the devil, philosophy, nature, war, suicide, even national cultures. One thing is certain, though: it's always dark.

Nachtmystium guitarist/vocalist Blake Judd follows suit by dressing his music in images of skulls and desolate landscapes. As co-founder of Sycamore-based Battle Kommand Records, he's released work by such Satan-loving acts as Cleveland's Nunslaughter, Vancouver's Gloria Diaboli and Finland's Archgoat. Nachtmystium's own discography includes the tangle of demos and EPs expected for underground blasphemers, including splits with some of American black metal's most respected names (Xasthur, Krieg), and in 2005, Judd was part of black metal "supergroup" Twilight's sole album.

As the band's only remaining original member, the Wheaton native insists that despite these connections, today's Nachtmystium does not play black metal. Judging from their newly-released fourth LP, Assassins: Black Meddle Part I (Century Media), that's not just iconoclast posturing.

Furthering the title's psyche-era reference, album intro "One of These Nights" crossbreeds Pink Floyd's "One of These Days" with the identical rhythm of Black Sabbath's "Children of the Grave." From there, Assassins vacillates between black metal's breakneck speed, accessibly melodic metal passages and a sludgy miasma typically associated with the post-hardcore scene, all laced with bright solos and trippy atmospherics that reinforce the band's love of '70s-style psychedelia. Slightly reminiscent of forward-thinking Norwegians Enslaved, it's one of 2008's must-hear metal albums, transcending the limited appeal of Judd's lo-fi black metal peers with engagingly diverse songs and powerful, prickly production by Minsk's Sanford Parker and Chris Black of Superchrist, Dawnbringer and Pharaoh.

Nachtmystium soon hits the road with the indie-friendly doom duo of Boris and Torche. In anticipation, an edited conversation with Blake Judd follows.

Q: You grew up in Wheaton. Is that where you started playing music?

A: I started playing guitar when I was about 12, but I was never really in a band until I was 16 or 17. The first four or five years of Nachtmystium's existence were definitely run out of my parents' house (laughs). I'm sure you know a little about Wheaton. It's not an unsurprising place for a black metal band to pop out of.

Q: Sure, it's the land of many churches. Assassins is a higher-profile release than you've ever had, so do you feel all your work in the underground is paying off?

A: Yeah, I think it came to a point where we outgrew where we had started off. I started my own label, Battle Kommand, and did a lot of the Nachtmystium records, which had originally come out on real small labels, much like the one I run. Because we never had contracts or legal obligations to those labels (it was always a handshake deal, they'd make a thousand discs and give me a hundred or something), I was able to repress those records. I did all the pressings for our last full-length, Instinct: Decay [2006], and it did things that we honestly did not think it would do. We wound up selling over 10,000 copies of it and I realized that the band had outgrown the label. It was time to move on, because we wouldn't be able to tour the way we do now, we need more money to work with. That's why we decided to step up and go to a bigger label.

Q: Is there going to be a Black Meddle Part II, then?

A: Definitely. The whole "Part I" and "Part II" thing came from our producer, Chris Black, who's been working with us for years. He's got a very strange sense of humor about things, and we only have a two full-length deal with Century Media (which is why we chose their offer, we wanted a short deal). Once that was set up, he goes, "Dude, you should do 'Part I' and 'Part II,' the Century Media years or whatever you want to call it." Given the way things are going with the label so far, as long as we keep making them happy, they're making us very happy.

Q: You guys have actually toured pretty frequently on your own, though.

A: I think that was part of our appeal to the label, too. We worked hard before we needed to be working hard for anybody else. It was obvious that we were kind of hungry for it.

Q: Over the last few albums, you can hear Nachtmystium working toward a unique sound. Can you explain why you don't feel you're a black metal band anymore?

A: I really respect what I view to be real black metal, and real black metal to me is more than just a sound. It's a lifestyle, it's an ideology, and I walked in those shoes for many years. Now, granted, it has also become kind of a joke. It's so accessible these days, and it attracts a lot of young people. Not that I wasn't young when I got into it, but I got into it in the days before MySpace and the internet explosion. Bands like Emperor, Dimmu Borgir and Cradle of Filth were around, but they were very much underground bands and you couldn't find their music easily. In time, I was soured on it because what I always really liked about it when I was younger (I'm sure part of this has to do with growing up, too) was that it was very special and unique to me. I did not have a group of friends who were into it, people didn't pave the path for me, I found it on my own and got really into it.

But back to your question, I look at a band like Watain. They're the real deal, man. They take it very seriously, there's nothing cheesy or fake about it. To me, that's what real black metal is, it's a whole "counter-life" situation. It's not for everybody, basically. I think that what we do isn't tied into anti-religious sentiment so much anymore, we're writing more about societal issues, things that we deal with in our personal lives. Also, the image has completely changed, and the influences that we're bringing in... as a fan of black metal, I'm offended by someone who calls their music black metal and incorporates outside elements. In a sense, I'm still a purist when it comes to being a fan, and I think it's disrespectful to the genre to label something like what we're doing. Bringing essentially a hippie rock influence into our sound goes against what I think is real black metal.

Q: Can you talk about what you call your "hippie rock" influence?

A: That goes back to my earliest memories of listening to music. My parents grew up during the '60s and they were very into Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath... I could go on for hours. The first concert I ever saw was the Allman Brothers in second grade, and they're very much a psyche/jam band. I grew up with that element present in my life, and as I got older, I revolted against it like any teenager who rebels against what his folks are into. Once I grew out of that phase, I realized that I was raised with all this great music and I went back to it, and these days, I couldn't tell you the last time I put on a black metal album that wasn't one of the first three Bathory records or a Venom record. I just don't listen to it anymore, and it's not really where my heart's at musically. I was so entrenched in all this extreme underground metal for so long that I've kind of gotten sick of it and my eyes have been opened in the last five or six years. There's so much other great music to get into.

This is the stuff that I grew up with and made me want to play guitar in the first place. It certainly wasn't listening to the early Emperor demos that made me pick up a guitar, it was listening to Jimi Hendrix when I was six years old. I was a huge Beatles nerd when I was a little kid, that was the first band that I really connected with. Naturally, it's so easy, the early Beatles stuff is so sing-songy and poppy, it caught my ear and I progressed from that. I'm sort of coming back to my roots, and I think that's a more honest place for me to be as a musician. I'm not trying to hold on to something that I'm really not into because it's convenient. How easy would it be for us to slather on corpsepaint and walk around a be Watain? We could fake it, I could dye my hair black and wear spikes and leather everywhere I go, but that's not really me. I think it's a challenge to come from what we've come from. Given that we've built a name for ourselves in that world, a world that is very unforgiving to people when they change, it's so much more challenging and rewarding to be able to "meddle" with black metal as much as we are and still be somewhat present in that world.

Q: You've also made inroads with the indie doom scene, which is a big force locally right now, and you've worked with Sunn O)))'s Greg Anderson (owner of hipster doom label Southern Lord).

A: Greg stepped up to bat for us when I did that Twilight record a few years ago. It's funny, I read everything on the internet, and I saw people being like, "Oh, this band was just put together to sell records." The reality is that record was recorded for a year before we even knew Greg Anderson. We did that on a $1,000 budget. To get five guys to San Francisco, the most expensive city in the country next to New York or L.A., and make a record, that was purely an artistic endeavor for all of us.

But back to your question, I started to dabble with the doom thing around 2001 or 2002. By '03, I was really getting into the Southern Lord stuff, and if you remember, that was before the whole Sunn O))) phenomenon happened. I kind of caught the tail end of that underground scene, and at that time it wasn't the hip thing at Reckless Records or whatever. I started networking with people in that realm of music, which as around the same time that I was coming to terms with the fact that I was burned out on black metal and death metal as well. I embraced it because there is definitely an element of rock in that music, especially the old Southern Lord catalog. I mean, that guy was putting out Desert Sessions records, and I'm a huge Queens of the Stone Age/Kyuss nerd, so it was cool to see an extreme metal form taking on rock elements. It was a way for me to start to step back to my roots without completely abandoning metal.

Once I started hanging out in the city more often, hanging out in bars like The Note when they did all those doom shows there, I started meeting people. It was cool, there was a scene for that stuff here, and the people weren't your black metal people, all fighting with each other all the time, who's going to smile less than everyone else (laughs). So, I started as a fan in that scene, and when Greg Anderson popped up while we were doing the Twilight thing, he just called me out of nowhere. We wound up talking for three hours, and about two and a half hours of that we were talking about ZZ Top and stuff. Southern Lord put out the Twilight album, which was one of the very first black metal things he'd done. I know he did Urgehal and Tangorodrim, but neither of those bands really sent a ripple out like he felt Twilight did. But I also feel that scene is a lot like the black metal scene. It got very popular and trendy, and now you've got a whole slew of shitty bands. I don't really get excited when I go to a local show and see a bunch of dudes I don't recognize wheeling in 800 pounds of Sunn amps. That's cool, but it's kind of burning out for me.

Q: Assassins is actually a great "headphone" album.

A: I definitely wanted that element to be there, but [producer] Sanford Parker is fully to blame for that aspect (laughs). He's a great engineer and in my opinion, he's got the most similar taste in music to mine of anyone I've ever worked with. I think he feels things in music that make him love it the same way I do. In that regard, we didn't really even have to talk about it. He knew what we were going for and we knew what he was capable of. He opened me up to a lot of new ideas that I hadn't explored before and in a lot of cases wasn't really aware the possibilities were there. It was very natural, nothing was forced in the studio. It's funny, some of these people I've been talking to at magazines the last couple of weeks have been like, "That must have been a really stressful recording!" No, if you sat in there and watched the process, you'd be like, "How did these clowns create something like this out of it?"

It was a mellow, relaxed environment, we all got along, there was not a single argument in 14 days of being together 24/7. I can't say I've ever talked to a band that never fought in the studio, but we have never fought in the studio ever. That's not how we roll, man, that's fun, that's why we do this, to get in and make records. Why people would fight in those circumstances is beyond me. At the end of the day, I have what we call "veto power" because it is my band, and if someone brings something to the table that I don't like, I'll say it respectfully. Only once or twice have I ever shot down someone's idea, and there wasn't an argument. It's a natural, healthy band environment. Honestly, I've never really been happy with any of our records, to this day I think all of them could have been improved upon, but I'm very proud of Assassins and can't imagine anything about it that I would like to hear differently. I'm glad that it's being received well, but even if it wasn't I'd still be totally happy with it. But maybe that means we're doing something wrong, too (laughs).

Q: For your hometown record release show, you're playing with Sanford's band Minsk as well as Yakuza, whose Bruce Lamont plays saxophone on Assassins. I feel like Nachtmystium and Yakuza are almost kindred spirits in pushing the boundaries around here.

A: Definitely, and they're love-or-hate bands, too. Yakuza are friends with the same people we are, we hang more around that kind of indie-stoner-doom scene than anything. At the same time, our bands are both completely different from about 90% of what those guys are doing. Bruce is a really ambitious, open-minded guy. I mean, it really takes a lot of balls to play a fucking saxophone in a grinding metal band.

**************

Talking drums: The beat goes on for Mickey Hart

Drummers are expected to focus on rhythm, but Mickey Hart's dedication cannot be compared to that of your average skin basher. For him, rhythm is seemingly vital to life itself.

Author, musicologist and social activist Hart is best known to rock audiences for his time in the Grateful Dead, where he and fellow percussionist Bill Kreutzmann explored polyrhythmic jams in concert segments known to fans as "Rhythm Devils." His acquisition of percussion instruments from around the world sparked an interest in global cultures, leading to collaborations with drummers as Nigeria's Babatunde Olatunji, Brazil's Airto Moreira and India's Zakir Hussain.

Hart believes in bringing people together through rhythm. His 1991 album Planet Drum united these artists and more in a groundbreaking celebration of multicultural drumming, which earned the very first Grammy for Best World Music Album. For the opening ceremony of the 1996 Olympic Games, Hart composed a piece that was performed by 100 percussionists, and as part of 2004's Earthdance festival, he organized a drum circle in California that was recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as history's "Largest Drum Ensemble." Aside from performing, he works with the Library of Congress' American Folklife Center to preserve its collection of decaying analog field recordings and campaigns for recognition of rhythm as a source of neurological healing,

In recent years, Hart formed the Global Drum Project with Hussain, Nigerian talking drum master Sikiru Adepoju and Puerto Rico's Giovanni Hidalgo, and he teamed with Kreutzmann in an ensemble dubbed the Rhythm Devils. The new DVD "Rhythm Devils Concert Experience" (StarCity) documents a 2006 concert at the Chicago Theatre by the latter group, which includes guitarist Steve Kimock and former Phish bassist Mike Gordon. Featuring a number of new songs co-written with Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, it's actually the first release to bear the Rhythm Devils name since the score from the 1979 film "Apocalypse Now."

The Mickey Hart Band (with Rhythm Devils alums Kimock, Adepoju and vocalist Jen Durkin, plus The Meters' bassist George Porter Jr. and renowned Latin drummer Walfredo Reyes Jr.) performs Saturday at the Lake View Music Fest in Chicago. Following is an edited conversation with Hart.

Q: How do you feel about the Rhythm Devils DVD?

A: I like it. It's really the genius of Jeff Glixman. It's his thing, he really wove together all those beautiful images and the songs in a very mystical way.

Q: Can you tell me about the band?

A: Rhythm Devils is me and my associate Bill Kreutzmann, Mike Gordon, Steve Kimock, Sikiru Adepoju and Jen Durkin. That morphed into the Mickey Hart Band. Mike has been replaced by George Porter, the amazing bass player from The Meters, and Billy's position is being filled by Wally Reyes, who's an amazing drummer, we have great chemistry. It's basically the same as the Rhythm Devils without Bill and Mike.

Q: It's just one of the Rhythm Devils.

A: Right, but now we've added Kyle Hollingsworth from The String Cheese Incident on keyboards, which adds another dimension to it. I'm real excited about this combination of musicians, it's going to be very exciting to get on the stage. We haven't actually played together yet.

Q: On the "making of" portion of the DVD, you start to say that Chicago has a lot of memories.

A: Chicago was usually last on the tour, at Soldier Field, and of course the Field Museum is there. These are favorites of mine. It was always the place to stock up on amazing drum equipment. The people there, it's almost like New York as far as really being into the music and rabid (laughs). It was always a wonderful town for us.

Q: Do you remember anything specific about the show you filmed for the DVD?

A: It was filled with energy and it had that kind of vibe to it. We played really well, and it seemed to be representative of who we were at the time. It was a work in progress. We hadn't played many shows then. The songs now are much more developed in the live performance. It's an aural snapshot of us that's beautiful, and Glixman brings it alive and makes it an experience, not just concert footage. It's not just a bunch of guys up there playing, now you can go to these beautiful places visually by the footage that Jeff has woven into the fabric.

Q: When you're composing, how do you balance leaving space for improvisation with more straightforward song segments?

A: That really has a lot to do with the sensibilities of the musicians who are playing. That's the composition. You pick the musicians you want to play with that have that sensibility, that know exactly what you're talking about, where to let the song go and create something in the moment, then where and how to bring it back to at least make it some kind of recognizable music so people can hold on to it and you can play it again. I guess that's a skill that's learned when you do it many times. That is, you learn the jam, which is a headspace in itself, and you also learn how to deliver a song within that framework.

Q: Although your instrumentation is complex, you still have regular verses and choruses in your songs. You mention having something recognizable, so is that what you're serving by having those?

A: Well, not really regular choruses and verses. My songs don't really have a lot of chord changes, they're more like a chant or in a modality. So, no, it's not in that respect. It's that there are words to these songs. They were penned by Robert Hunter, these are some of the best works he's done for many years, I think. There has to be a setting for the words, and that's where the songs come in. All the transitions in between, kind of dancing with the music in real time, is when the magic happens, and of course, that's what you always court and you want on a nightly basis. You have to set the stage for the magic, and if you do that with a combination of songs, we'll say that's order. Then you go to chaos, and back and forth, from chaos to order, order to chaos. That's what the ebb and flow of music is about for me.

Q: Your nonperforming passions are centered around music as well. Can you tell me about your initiative to promote drumming as a healing agent?

A: It's about the neurology of music. We know that music, rhythm, sound, controlled vibrations affect brain wave function. What we don't know is exactly how it affects it, how we can repeat that on a daily basis and make these feelings that we get sometimes from music available so that it becomes medicine. That's what science is now delving into, how the brain works before, during and after an auditory driving experience, which is what music does to the auditory system, it drives the system. So that's the most exciting frontier in music now. Playing's really a lot of fun, but the neurological applications of music and rhythm for Alzheimer's, dementia, all the motor impairment diseases will be affected once the code has been broken. That's happening now. Read Oliver Sacks' book "Musicophilia," that just came out a few months ago. It talks about this very thing.

Q: You're also part of a larger effort to preserve recordings that are in danger of disappearing.

A: That resides at the Library of Congress. We've been recording sounds in the field since 1890. The whole history of recorded music lies in these archives, whether it be the Smithsonian or the Library of Congress or attics or basements around the world. They are decomposing because the medium on which they've been recorded is losing its life, so you have to find that rare, endangered music and digitize it before it completely turns to dust. That's part of what the Endangered Music Project is, to find these amazing musics and digitize them so they can be preserved and allowed access to for ages.

Q: Have you worked on anything that helped to revive interest in an indigenous culture?

A: Everything I do usually winds up that way. For instance, the music I found from pre-World War II Bali and Indonesia [released in 1994 by Rykodisc as Music for the Gods: The Fahnestock South Sea Expedition, Indonesia], that music was ripped away from them by the war. When it was given back by the Endangered Music Project, it was like a repatriation of their music. They started practicing this music that was only spoken about by their grandfathers. It became a rare and important cultural artifact that was given back to them finally after all these years. Proceeds go right back into the community, and they get their most valuable possession back, their music.

Q: That seems to go back to the healing thing, helping people come back together after the trauma of war.

A: Folk music, not art music, is all about that. It's all about prayer, it verges on the sacred. Some of it's secular, some of it's just passing time of day or talking about their life. But much of it is sacred music. It's their prayers. These are like talking books, so they contain thousands of years of evolution. It's not just a song, it's what the song means, it's a badge of identity for a culture.

Q: Has any one culture or instrument been of particular interest to you lately?

A: You bet. I'm back into the amazing chants of the Gyuto monks from Tibet, the monks that chant three notes simultaneously. I'm looking into my archives to find all the recordings of the monks I've made since '85 and trying to release them from the vault.

Q: Do you still feel that attraction to music that you did when you were young?

A: Of course. I have something to do with that vibratory world every day, whether I play or I listen to music or I dream about it or I think about how to dance with that vibratory world. That's what I do, that's what I'm coded to do. I feel as passionate as I ever have. My love affair with music will be forever. Of course, sometimes it wanes and sometimes it gets more powerful, that's the way of things, but it's always there. I mean, sometimes you hear something that just rivets your imagination and you can't get it out of your mind. That means you're totally consumed by the music. Other times you're more playful with it, you're trying to make forms out of it and birth songs, that's another kind of thing. There are different kinds of headspaces that you need to be able to attain to be able to have a life in music. If you're with music, if that's the ultimate thing, then it's with you and you are with it during your day. It's a lifestyle, as opposed to something that you listen to as entertainment. It's part of your nourishment, part of your food.

Post a Comment

<< Home